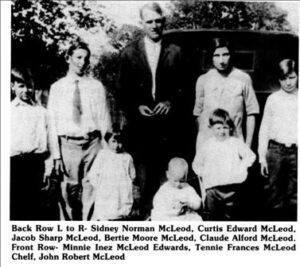

McLeod Family

McLeod Family History

“Hold fast,” a family motto since the thirteenth century, remains an attitude, seemingly-genetically transferred, which represents the tenacity and stubbornness of those who are of McLeod descent. Present day McLeod’s trace their ancestry back to the hardy Scotsmen who emigrated to North Carolina from the barren coasts of the Isle of Skye in 1770, settling in the Carolinas, the McLeod’s, accustomed to fierce and frequent battles with neighboring clans who sought to encroach on family lands, further distinguished themselves as Americans in the American Revolution and later as Southerners in the Civil War, determined once again to defend and protect land that they loved. It wasn’t until after the Civil War that McLeod’s moved to Texas to make homes for themselves and their families. Settling first in Cherokee County in 1877, the McLeod’s finally moved into the Augusta area in the early years of the twentieth century. Principally farmers rather than soldiers, the McLeod clan gradually established deep roots and began to flourish. The progenitor of the family who now lives in Augusta-Liberty Hill was Albert Sidney Johnson McLeod, son of William Alexander McLeod, so called after his father’s Confederate Commander. The first of the family to move to Texas, Albert Sidney was reputed to be a “religious man who was quick of temper, but [also] quick to forgive.” He fathered three children by his wife, Tennessee Ramey, the youngest of who was Jacob Edward Sharp McLeod, both in 1893, the patriarch of the present day Augusta McLeod’s. Albert Sidney, left a widower, soon married a second time, as was the custom of the time, to Mollie Foreman Robbins, who bore him two more children. Sharp McLeod, born in Augusta, spent his life rearing his own family of seven. A man of diverse interests and varied talents, Sharp could converse at great length on religion, politics, sports (especially baseball), deer, agriculture, a foxhunt, or the weather. Never at a loss for words, was Sharp, a tall, raw-boned man who walked habitually with a slouch, rarely seen without his somewhat shapeless felt hat. Willing to help anyone in need, he was generous with his time, his energy and his money. Until the inevitable infirmities of age forced him to resort to a pickup truck, Sharp worked his cattle from the saddle with a pair of dogs and seldom returned home before dusk. A man of great strength and stamina, he firmly and devoutly believed in the America work ethic. He insisted that his sons share in the work, and, like many families who lived on the land, no one was exempt from the field. Cultivating their crops with mules, Sharp and his sons worked fourteen-hour days, from daylight to black dark in order to provide for the family. Respected and loved by those who knew him, Sharp later in his life enjoyed a successful stint as a county commissioner. His success again lay in his willingness to work long and hard and in his spirit of conviviality. Of his seven children, only one son, John Robert, remained to live in Augusta. Following the lead of his father, John, too, reared his family in Augusta. Two of John McLeod’s sons, Bobby and Jerry, remained in Augusta to rear their families. Another of Sharp’s sons, Sidney Norman, after a number of years living in a number of places, returned to Augusta, the place of his birth, to retire on his farm in 1974. Two of his children, Kenneth and Delma, have chosen to make Augusta their home. Inez McLeod Edwards, oldest daughter of Sharp, has also returned to Augusta to live. Her daughter, Linda Richie, has, too, chosen to make urbanAugusta her home, as well as Linda’s son, Lawrence Richie and his wife, Julie. Occupying the land around and in Augusta for over one hundred years then have been McLeod’s. Just as the family ancestors loved their land and often found themselves defending it with their lives, today’s McLeod’s are devoted to the land. Defense in the eighties is fortunately limited to drought, fire ants, and taxes. From thirteenth-century Scotland come the traditions of “holding fast” against neighboring clans, imperialistic kings, and foreign invaders; down through time, through war, through economic hardships, through painful personal tragedy, the McLeod’s have indeed proudly held fast. Bringing Home the Bacon (Sidney) Norman McLeod recounts his own family experience of raising hogs that gives a new meaning to the phrase, “bringing home the bacon”. It seems that his father, Sharp McLeod, and a Mr. Miles both had a “claim” to the Neches River bottom that enabled them to graze hogs there during the summer months. The hogs were taken down to the river and penned up for a few days, during which time they were given corn. They were then loosed and allowed to spend the hot, dry summer months grazing on whatever fodder they could forage for themselves. When the weather became cool and time came for butchering, Sharp would engage Charlie Hopper, a man who owned “hog dogs” to help him round up the hogs that had spent the summer growing fat. Sharp’s hogs were identified (at least the first generation hogs) by a swallow-forked notch in the ear. Occasionally the notch encompassed the larger part of the ears, but never-the less, Sharp knew his mark when he saw it. Mr. Hopper and the rest of the hog hunters would venture into the river bottom. When the hogs were sighted, Hopper would loose his dogs, for the once-domestic hogs were now wild and did not return of their own accord. The dogs, well-trained apparently for hand-to-hand combat with a large fat recalcitrant hog, would rush up and grab a hog by the ear and hold him fast until Mr. Hopper could run over with rope and tie the animal up by his feet. The hogs would then be loaded into a wagon and returned to their former home for slaughter and provide meat for the family for the winter. Mr. Hopper received half of whatever he caught for his payment. The dogs, well, it can be assumed that they received their part of the bacon, too. The benefits of such an arrangement are obvious — hogs are fatted without expense. However, there are a few disadvantages: occasionally the now-wild hogs would attack and kill an unfortunate dog, and since grazing the hogs was not an uncommon practice, people who had need of pork often helped themselves. Never-the-less, this means of “bringing home the bacon” is an unusual one at the very least.